Malcolm Sargent

This article is based on my recent research into the life of Malcolm Sargent which I have found fascinating, intriguing and compelling in equal measure. I have read a great deal and talked to many people who have memories of him and people who knew him including Sylvia Darley, Sir Malcolm’s secretary for the last 20 years of his life. She has been extremely helpful and supportive.

This short biography aims to chart the story of how a boy from an ordinary family from the gasworks end of Stamford who became one of the best known and best loved musicians both in Britain and the wider world.

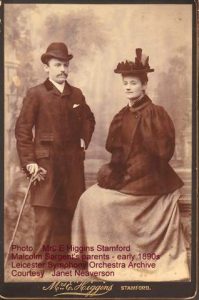

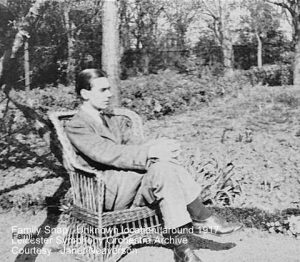

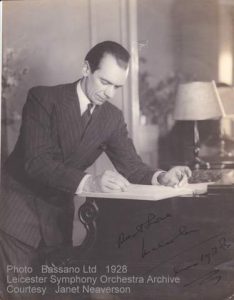

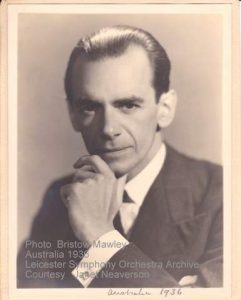

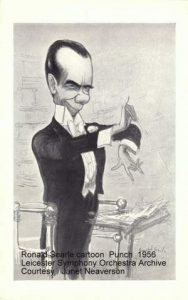

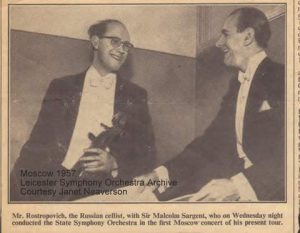

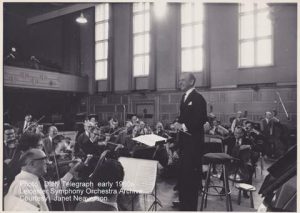

The photographs accompanying the article were kindly donated to the LSO archive by Mrs Janet Neaverson. They were originally collected by Olive, Malcolm’s cousin on his mother’s side. Additional material came from Malcolm’s sister Dorothy. The collection was passed down to Janet’s late husband Peter Neaverson.

Music, Music all the Way

Malcolm was born in 1895 and grew up in Stamford where his father, a clerk in a coal merchant’s office, was a musician of considerable talent who did everything he could to encourage music in his son. On Sundays dad was organist and choirmaster at St John’s church in the town. At the age of 8 Malcolm joined the choir and even then he knew he was driven by an obsession akin to a religious fervour. So intense were the feelings generated by music, on many occasions he was known to pass out when playing or singing.

Malcolm always had an eye for forensic detail. At 14 he had his first taste of conducting when, without notice, he stood in for a two hour rehearsal of the Stamford Operatic Society. People were astounded at his briskness and fluency. He further sharpened and progressed his musical skills under his piano teacher, the aptly named Mrs Tinkler, and later was articled at Peterborough cathedral. Until then he had been ‘single minded’ about music. Now it was total immersion. In addition to his articles he studied for a degree with Durham. He was never happier and in his own words, ‘It was music, music, music all the way.’

With his mastery of church, classical and popular music, he put himself at the centre of musical life in Melton Mowbray, where he was appointed organist and choirmaster in 1914. He was introduced into wider Melton society which was dominated by foxhunting. With his musical abilities, his natural wit and charm and the fact that he was never overawed by his social superiors, he soon became a guest at any number of parties and society occasions. He became a sort of unofficial ‘court entertainer’ to the aristocracy.

De Montfort Hall, Leicester was the setting for Malcolm’s big breakthrough in February 1921. He conducted the Queen’s Hall Orchestra in his own composition, An Impression on a Windy Day in front of Sir Henry Wood, the father of British conducting. Wood saw Malcolm’s talent and helped promote his career in the direction of conducting, rather than composing . Malcolm quickly attracted devoted followers, his buoyant personality enabling him to communicate his love of music to players, singers and audiences alike. His sense of theatre, elegant dress and sheer panache propelled a meteoric career in Britain and throughout the world.

A local business man and impresario Karl Russell was so impressed, with the ‘Windy Day’ concert, he arranged four concerts featuring Malcolm and their success led to the creation of the Leicester Symphony Orchestra (LSO) in 1922. Members of LSO, Melton Operatic, and Stamford Operatic, voiced their universal enthusiasm for their young conductor, ‘He turned nobodies into somebodies, small talents into sizeable ones. When he arrived for rehearsals he made everybody feel enormously glad to be alive simply because he looked enormously glad to be alive himself’.

Malcolm had a generous nature and spent freely. Outwardly he appeared extremely confident but underneath was an insecurity and a need to be loved. Women found him very attractive and there were many affairs – or more accurately flings – with young ladies from local music societies, middle aged aristocrats and later, even with royalty. He was ‘caught out’ in 1923 and had to marry Eileen, who he never loved. The couple had two children; Pamela and Peter. As his fame grew the affairs continued and the couple were divorced in 1946.

He could sometimes seem vain and arrogant making an uninhibited display of his enjoyment of the high life which unsurprisingly attracted hostility and ridicule. He was commonly known, not altogether flatteringly, as Flash Harry. There was some resentment from rank and file members of British orchestras who found him over controlling but equally many liked his clear and precise instructions. There was real hostility when Malcolm tried to tackle fundamental problems in the orchestra.

The London concert of Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic in 1930 made a deep impression on him and sent shock waves through the musical establishment. It was abundantly clear that the sound of the NYP was leagues ahead of that of any British orchestra. Malcolm was convinced that the way to achieve such standards, however unpopular, was to adopt Toscanini’s practice of using short term contracts so that players who were not up to the job could be levered out. There was a huge improvement in standards but the resentment generated blighted Malcolm’s career for many years.

He remained extremely popular with choirs and the public, almost invariably attracting capacity audiences. He gained respect when during the war he took on a punishing schedule of ‘Blitz Tour’ concerts, bringing cheap morale boosting concerts to thousands in devastated industrial areas. Over his career he gave countless children’s concerts, often in the poorest areas of cities. Both served to increase his popularity but it was his appearances on the BBC radio programme, the Brains Trust which earned him recognition far outside the bounds of classical music.

To many listeners, he was the common sense voice of the man in the street giving lively answers and generating a full post bag whatever the topic. New audiences were attracted to classical music. He did more in this direction than any other musician and in 1942 his superstar status was confirmed when the British Council called upon him to take a series of concerts and talks in neutral countries. He was soon dubbed ‘Britain’s Musical Ambassador’ in the press. After the war he continued taking every opportunity to promote Britain and British music on his many overseas tours. He was knighted in 1947.

In the same year took over the BBC Proms which he quickly put his own stamp on; the excitement of the Last Night being his creation. He conducted his 500th prom in 1966 and in the final years, the old ‘Flash Harry’ jibe was turned round by thousands of adoring Prommers chanting and singing, ‘We want Flash! We want Flash!’ He died of pancreatic cancer in 1967, his death provoking a remarkable demonstration of sorrow and admiration. A lifetime of great music making had won him the loyalty, respect and affection of countless music-lovers worldwide. What they loved most was his irrepressible love of music and his irrepressible love of life. There was a real sense that a great force for joy had been taken from us.

Sam Dobson – with thanks to Thomas Armstrong, Charles Reid, Richard Aldous, Sylvia Darley and others

Useful link; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Malcolm_Sargent